Before you get airborne

I used to fly helicopters, and we always used to say: “I’d rather be down here wishing I was up there, than up there wishing I was down here!”. Pre-flight checks are more important than flying: you could do one without the other, but never the other without the one. Those were the days!

I used to fly helicopters, and we always used to say: “I’d rather be down here wishing I was up there, than up there wishing I was down here!”. Pre-flight checks are more important than flying: you could do one without the other, but never the other without the one. Those were the days!

I’m working on helping take three businesses to market at the moment. To put that in context, all are existing businesses where we’re planning radical departures from history, and each will or should reach in the region of £1m run rate by the end of month twelve. So there are new markets to identify and propositions to craft, new organisations to be built, and new revenue and business models to define.

Exciting stuff but it’s easy to be amazed at the astonishing proposition you’ve devised, marvel at the huge market you’ve identified that no one else has spotted, and believe your own plan. Guard against Entrepreneur’s Bias, and check everything before you and your new venture get airborne.

I’m writing about the primary long term market trends elsewhere, so I’m not going to cover those external aspects here, but rather to look inward at some of the headline characteristics worth thinking about when reshaping a business or crafting a new one. That said, you have to start outside first because if you don’t know where an accessible opportunity lies, then you’re not ready to shape a proposition and the organisation to deliver it. Check your anticipated destination and the weather, before doing anything else.

The Headline Checklist

Here is my checklist of the things that I look at when reviewing any new plan. Please get in touch if you have favourites to add. None of these is likely to be new to any reader, but I find it useful to have the list compiled into one checklist to run through when contemplating a plan or during the journey to market.

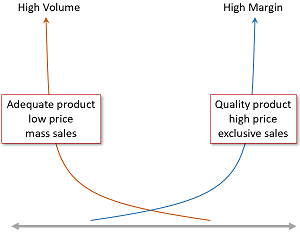

Are you selling on price or excellence?

Are you selling on price or excellence?

This question is rarely addressed firmly at the outset, yet it matters hugely. All aspects of the proposition and organisation will need to be different depending on the choice, and it can be catastrophic to end up in the middle, with the problems of both and the advantages of neither. This is sometimes referred to as the Bankruptcy Bucket.

Consider two things as examples:

Volume of sales – if you’re competing on price then margins will be tight, and so you will need to be focused on reaching volume with few errors. If you’re competing on excellence then margins should be higher and volums lower.

Time spent with the customer – high volume, low margin sales require a light touch, unlike propositions at the quality end of the scale, where customers expect to get more personal treatment. To characticture the two: one will need process; the other needs people.

So business models must be very different, the way of selling and delivering need to be different as well. The danger is not to know and not to have understood the implications. A worthwhile cautionary tale is “How Encyclopedia Brittanica was blown to bits“.

Gross Margin vs Management Style

Gross Margin vs Management Style

This leads on inevitably to the link between management style and gross margin. Think: Pencils. If you’re in the business of making pencils then gross margins are tight, you have to make and sell container loads of them, and management style is all about getting all the detail right, all the time, every time, day in day out.

On the other hand, if you’re in the business of using pencils – artists, musicians, authors, architects, designers – then the gross margins are far higher, or should be, and the management style should be all about nurturing the individual, the ideas, and matching creativity to the opportunity. Again, one is about process while the other is about people.

It is striking how closely management style is linked to gross margin in terms of where the time and attention has to be focused, operationally, at least. Of course, what often gets mixed with a high gross margin business – licensing, say – is speculative investment in the next big idea, and that usually means there are two management models to run, side by side.

Costs of Sale

One small aside here, from a dyed in the wool entrepreneur who’s sparred with many accountants over the definition of costs of sale: I’m expressing this as I see it and have found it valuable; accountants may differ.

As an entrepreneur, I need to know what costs are mathematically linked to sales – what more spending is required and must happen as sales rise, and which will automatically scale back when sales are lower. Defining costs of sales this way means that I can see where my flexibility lies and where it doesn’t.

For example, the base salaries of sales people are in overheads, because they don’t automatically drop when sales decline. Commissions and bonuses, though, are in costs of sale, because they do. Structuring management accounts this way means that performance models driven by sales forecasts present more meaningful output.

Cashflow

Cashflow

Few entrepreneurs or investors can contemplate going to market with something significant without being driven by a cashflow. The greater the scale relative to the starting point, the more it’s driven by cash. For most of us, cash is the ultimate calibration of the performance of any significant journey, and there’s a long road to travel before that changes.

Over the years I’ve come to use two measures of cash during planning and to monitor live cashflow forecasts. I developed these a long time ago and they’ve stood the test of time and a wide range of circumstances, and both adjust automatically to the scale of the business involved. They tell you where the pinch points are and when problems are heading your way.

Worst case intra-month (£) : [Opening Cash] minus [Total Monthly Expenditure]

This highlights what would happen during a month if all outgoings has to be paid before any income is received. In short, as soon as this turns negative, Management must begin to control the timing of payments depending on the receipt of income. This is the moment when short term issues and external factors take over and events start driving the business.

Cash cover (%) : [Opening cash] divided by [Total Monthly Expenditure]

This provides a leading indicator of problematic times ahead with at least some time to take avoiding action. When it drops to 150% it indicates that there’s enough cash to cover a month and a half of expenses – six weeks. I’ve found that 150% is something of a magic number and must be taken seriously if a forecast indicates that this could be breached.

Sometimes the threshold may need to be greater than this, for example in a business with excessively lumpy and unpredictable timing of receipts due to being dependent on a small number of large deals. In the great majority of cases, I’ve found that 150% is the point where urgent action is required.

Timing Cycles

It’s crucial to understand the implications of two business cycles before you head to market as well as monitoring them along the way. Each has a critical effect on the project effort and resources; the two often conspire together.

Sales Cycle – rather obviously, this has an impact on many things in a developing business: recruitment in Sales, marcoms effort, cashflow, etc, etc.

Investment Cycle – again, obviously, the gestation period of any investment, from start to finish, impacts many things.

So far, so rather obvious. The impact is magnified when the two act together, as they would in any investment that is expected to drive revenues, when one must be added to the other.

Go-to-Market Phases

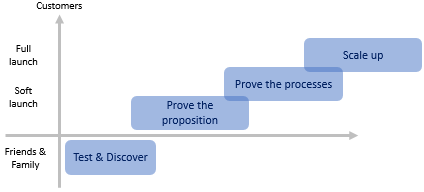

I’ve often been asked how to structure going to market, and it does suprise me how few teams plan the effort, just preferring to get going and see what happens.

There are three distinct phases to manage, and each has very different characteristics and objectives, and delivers crucial information that underpins the next in the sequence. Don’t try to boil the ocean on Day One.

Test & Discover – Planning is essential and it pays to do plenty of thinking, workshopping and modelling at the outset, but this is theoretical and prone to confirmation bias. Entrepreneurs are always eager buyers of their own proposition. Worse, they often misjudge just how far ahead of the market they are – they’re steeped in what they’re doing but outsiders are not. How many businesses have we all seen that have gone to market too quickly, and run out of runway before the market has caught up?

New propositions and ideas must be tested out. This is best done in careful and measured stages through the planning process, a few people at a time in order to have new and fresh observers to test and comment on adjustments made after earlier outings. Friends and family are usually the starting point, then market observers, and lastly friendly, potential customers.

Customers to Prove the Proposition – A friend of mine once said that the first few customers teach you more than you ever knew, and it’s wise to regard everything as unproven and up for radical change until you’ve successfully sold to a meat eating customer, not a test or a pilot, but for real usage.

Typically, you take the first small handful very carefully, one at a time, and monitor all aspects of the sale and delivery. It would be natural to approach potential customers who you spoke to during testing and discovery, but that would not be a real test. Customers to prove the proposition should be fresh and unaware so that messaging can be validated as well as your own understanding of your target market.

I think it was Warren Buffet who said: “Business is about getting to know people who’ve never heard of you, and selling them something that meets their expectations and makes a profit”. It pays to understand these things before piling in and committing resources to something that may require the fundamentals to change. That knowledge could come from just three or four real customers.

Customers to Prove the Processes – With the first few customers in the bag you will have built some understanding and confidence in the fundamentals of the proposition, revenue model and price point, sales cycle and delivery requirements. These things give you the information you need to work out how to set up the organisation and the processes required to get the show on the road.

Customers to Prove the Processes – With the first few customers in the bag you will have built some understanding and confidence in the fundamentals of the proposition, revenue model and price point, sales cycle and delivery requirements. These things give you the information you need to work out how to set up the organisation and the processes required to get the show on the road.

Don’t get ahead of yourself, though – take it a step at a time, and build proof. Keep ideas fluid and run just fast enough to test out what you’re doing, and build that proof. This might be done through the next ten real customers.

Now you can press forward with more assertiveness: start to pull in the Collective Lever, gradually feed in the power, and ease forward on the Cyclic.

The Bottom Right Hand Corner Problem

I’ve lost count of the number of business plans for companies going to market, that have ludicrous performance in their final year – net profit over 50%, and millions in surplus cash. Yeah, right. Faced with a financial model from someone setting out to take a business to market, I always look at the numbers in the bottom right-hand corner – do the ratios make any sense at all? In so many cases, that one simple test avoids the need to read any further.

I’ve lost count of the number of business plans for companies going to market, that have ludicrous performance in their final year – net profit over 50%, and millions in surplus cash. Yeah, right. Faced with a financial model from someone setting out to take a business to market, I always look at the numbers in the bottom right-hand corner – do the ratios make any sense at all? In so many cases, that one simple test avoids the need to read any further.

The common cause of the inflated, unrealistic performance in later stages is that the model has simply been multiplied – all the numbers have just been grown over time, when that isn’t what really happens. Change is what happens as growth takes place. Tasks that used to be a part of someone’s job now need to become the responsibility of a full time head. Teams grow and layers of middle management are needed. The structure of the organisation has to change and not just get bigger.

A sales plan with revenue numbers only, is not going to show the scale of the tasks involved, and the nature of the organisation required. So numbers and timing of new customers are needed, and from this you can start to build up a picture of the sales team required and customer base that needs to be supported. Bear in mind that you never win every customer you target, and so the pipeline will always have more customers to be engaged than actually feed into the revenue numbers, and so it goes on. Organisational change will bring those fat numbers down into the real world.

Business Model

Business Model

…and finally: the business model! Who does what, supplies what, pays what, gets what?

-

- Flexibility to change and adjust to change?

- Cash positive or cash negative?

- CapEx vs OpEx?

- What are the key constraints?

- Where are the risks: commercial, operational?

- What are the external dependencies?

- Where are the scaling issues?

- Where does it really build enduring value?

- How does it flex if things go better or go worse?

Also:

Blog These conditions require skillful driving

Blog Make Believe Startups

Blog Are we nearly there yet?

Blog The future began a while ago

Blog Can entrepreneurialism be taught?

Blog Human engagement is a big opportunity

Blog The Good, The Bad, and The Surreptitious

and

|

|

Peter is chairman of Flexiion and has a number of other business interests. (c) 2019, Peter Osborn