Last Updated on

Everyone’s been obsessed by technology

Technology has been the entrepreneurial and investment mantra for more than a generation. Perhaps this is because so many pivotal technologies emerged in the post-war years and got fuelled by the nascent venture capital industry, and that led, in turn, to the fokelore that the big opportunities lie in technology.

Technology has been the entrepreneurial and investment mantra for more than a generation. Perhaps this is because so many pivotal technologies emerged in the post-war years and got fuelled by the nascent venture capital industry, and that led, in turn, to the fokelore that the big opportunities lie in technology.

At least one generation of entrepreneurs, possibly two, has grown up with technology being held up as the holy grail. Swathes of the investment community describe themselves as technology investors, specialising in this technology or that. That folklore became deep seated, with the ledgendary backdrop of Silicon Valley and all those meetings at Rickey’s Hyatt, just off 101 in Palo Alto. When I went there the place wasn’t anything to write home about, but the conversations were stellar.

Is technology really where the big opportunities lie? The evidence points elsewhere.

Technology opens the way, for sure

There have been some huge, society-changing technologies, without doubt. The Industrial Revolution was built on the technology of producing power from coal and steam, and this had a century-long impact on society until the rise of the internal combustion engine in the second half of the Nineteenth Century.

There have been some huge, society-changing technologies, without doubt. The Industrial Revolution was built on the technology of producing power from coal and steam, and this had a century-long impact on society until the rise of the internal combustion engine in the second half of the Nineteenth Century.

The technology of heavier than air flight made an impact, as did radio. Arguably, though, the next really big technology with similarly far reaching impact was the digitalisation that began to take hold with the invention of the silicon transistor in the late 1940s.

As with steam, the impact of digitalisation was far reaching, and the whole story has yet to be told. The development of TCP/IP techniques at Darpa to produce a communications system that would be resilient to attack, gave rise to the Internet, and we all know what happened with that. I received my first Internet email in 1986, and I have to say that at the time I didn’t forsee the unfolding revolution it represented.

Out went a whole industry of analogue circuitry over time. Mobile handsets replaced the old style phone with its vast, mechanical, clackerty-clack telephone exchanges. Look at what’s hppened to photography, and music isn’t the same, either.

VoIP is a classic case of a technology causing large and widespread disruption, but the technology was first seen in 1973 in the Arpanet, and it didn’t make it out of the labs with any seriousness until Skype launched as a business in 2003, when it started to create a big wave of adoption and value creation, leading its acquisition by Microsoft in 2011 for $8.5bn.

It’s business innovation that delivers the benefits

Since Skype showed how you could create a business around the technology, many others have used the VoIP to create businesses in other sectors, from video conferencing to eCommerce web chat, corporate collaboration platforms, you name it. Some of these are services that didn’t really exist before, but many of the new applications disrupted established markets, like traditional PSTN telephone services, causing that whole industry to be redefined and restructured.

The successful development of the technology was a necessary step, but twenty years elapsed before the business innovation occured in the right circumstances, driven by the right people, to deliver the benefits and create the wave of value building. This same process is visible elsewhere, demonstrating that business innovation is where big opportunities lie.

The successful development of the technology was a necessary step, but twenty years elapsed before the business innovation occured in the right circumstances, driven by the right people, to deliver the benefits and create the wave of value building. This same process is visible elsewhere, demonstrating that business innovation is where big opportunities lie.

Air travel was reserved for the military and well off until Freddie Laker, perhaps others too, devised the low cost business model. Edison was the innovator who took electricity generation and centralised it in a power station, distributing it to customers who would otherwise have needed their own generators. Steve Wozniac was the technologist, but it was Jobs who devised the innovations in target markets and pricing that created the huge wave of value. His choice of $799 for the Apple II was pivotal because $800 was typically where purchasing authorisation jumped seniority in Corporate America.

The big modern world upheavals have come from business models

Big upheavals don’t often come from technology, as such, but from devising a successful business model that allows that technology to flourish. Steam power was known for some time before it became widely deployed and began to drive the changes of the Industrial Revolution through the businesses of the railways that worked out business models to ship people and cargo, and factories to mass produce what had been available only from individual craftsmen.

Rail opened up the American West enabling ranches to sell and ship cattle to the big markets on the East Coast. On the way back, they took goods ordered through the new mail order catalogues, which were developed by Tiffany and Sears. Henry Ford’s cars were “any colour so long as they’re black” and he standardised all the parts, even defining the packing cases suppliers used so that he could dismanltle them to make floorboards for the cars. The technology is a necessary but insufficent component. The big waves of opportunity come when the right business model harnesses technology at the right time and in the right way.

Watch out for the curved balls

New business models unseat the unwary or those who’re slow to see the implications, but these pitfalls are usually about the business models not whether the technology will do what’s claimed.

For decades, the assumption was that quality was the holy grail and this is where effort and investment was directed. Who would have thought that convenience would have been so much more important until this was proved emphatically by Amazon.

This 1999 interview with Jeff Bezos is fascinating and well worth watching, even watching again if you’ve already seen it.

Examples of misreading the implications of technology for business models are many. Encyclopedia Britannica was established for 250 years, but Encarta and digital media unseated it in as many weeks. The Swiss watch industry was built on handcrafted excellence, until the Quartz Crisis showed them how Asian businesses could produce and sell highly accurate digital devices in volume, at a fraction of the price of their masterpieces. It was existential, but their response was to form Swatch and join in the mass market.

| The Fire That Changed an Industry |

| About 8 p.m. on March 17, 2000, a lightning bolt struck a high-voltage electricity line in New Mexico. As power fluctuated across the state, a fire broke out in a fabrication line of the Royal Philips Electronics radio frequency chip manufacturing plant in Albuquerque. Plant personnel reacted quickly and extinguished the fire within ten minutes. At first blush, it was clear that eight trays of silicon wafers on that line were destroyed. When fully processed, these would have produced chips for several thousand cell phones. A setback, no doubt, but definitely not a calamity. Read on…. |

Kodak and Polaroid both misread the business model of offering digital immediacy and convenience to their mass market. Microsoft misread the significance of the Internet, and only just managed to muscle a place for itself at the last moment.

The implications for big business of a small and seemingly insignificant problem with a factory air conditioner were correctly understood by Nokia but comprehensively missed by Ericsson, leading their mobile phone business to implode and get sold to form the basis for Sony Ericsson. A cautionary tale, and then some!

Some models may be time limited

Time and again, the action is around the business model, and that’s where the big waves of opportunity and danger lie. Sometimes, what the business is doing appears to be ok but objective thinking says it could be time limited. I can remember contacts of mine in banking being really worried about sub-prime at least two years before that proved unsustainable. Similarly, friends poured scorn on WeWork long before its recent collapse.

Google has a fantastic looking business model built on owning more and ever more data about what we’re all doing, but does seem rather like the three card trick. They’re not alone in appearing to sucker in people to give them data by flashing enticing services. Google will last in some huge form, I’m sure, but the headwinds are gathering strength everywhere.

The subscription business model is starting to creak as more choice is leading to saturation and fatigue, with consumers starting to resent how many subscriptions they have to take out to get the content they want. It won’t be long before new pay-for-use business models start to gain traction and unseat the subscription services. It’s that desire for convenience again.

Regulatory arbitrage has always been a game of cat and mouse between innovators who spot a gap and regulators who close them. Part of the Fintech boom has been fuelled by the light regulation applying to nimble new entrants compared to the heavy regulation on the shoulders of incumbent banks and financial firms.

The platforms that have been positioning themselves as pivots in the Gig Economy are really playing this arbitrage game, and it’s been interesting to watch them come under pressure from regulators seeking to close the regulatory gap. As with some of these other business models, you can see the signs that their advantage has time limits and may not be sustainable.

At the very least, Uber’s economic advantage will be significantly reduced by each regulator that imposes the same obligations on them as on regular cab companies, and the same employment costs. A similar regulatory fight is underway with publishers like Facebook and Google, who claim they’re not publishers and not burdened by the same obligations. It’s a slippery slope. Uber is losing their battle one city at a time, and the media platforms are having to recruit new teams one by one to address the issues as they hit. Death by a thousand cuts?

Big, big opportunities lie ahead

There are lots of big opportunities out there just waiting for innovators of business models. The shift from ownership to pay-for-use is a big one, with some far reaching consequences as new models emerge and old ones get sidelined. The automotive sector is one example, with the generational decline of ownership becoming established in developed economies.

New business models will be needed to engage customers in very different ways. The days appear to be numbered for the traditional consumer facing dealership with its much loved car salesman. Insurance also needs a re-think, since pay-for-use vehicle insurance won’t be sold directly to the driver. Some estimates put as much as a third of high street insurers basing their business model on vehicle insurance, so the implications for incumbents are significant.

The shift to autonomous vehicles looks unstoppable, although it’s likely to have a slow on-ramp. This shift also creates big challenges around business models, and the whole sector is just beginning to grasp that sorting out viable technology is merely the qualification to enter that business race. Hardly any work has been done on business models, compared to the effort that’s gone into the technology.

The shift to autonomous vehicles looks unstoppable, although it’s likely to have a slow on-ramp. This shift also creates big challenges around business models, and the whole sector is just beginning to grasp that sorting out viable technology is merely the qualification to enter that business race. Hardly any work has been done on business models, compared to the effort that’s gone into the technology.

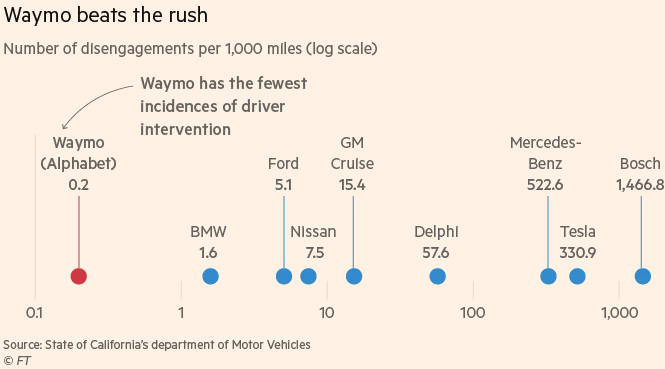

The hurdle of devising viable business models for engaging with consumers probably favours the likes of Uber and Google over traditional automotive OEMs, none of whom know how to do that stuff at scale. This explains why both have active av programmes, although Google’s Waymo is billions of miles in front, literally. They announced in July that they’ve driven 10bn test miles, and this graphic shows how far ahead their technology is (it’s staggering, actually). However good the tech is, they must solve the challenge of the business model, but my hunch is that Google is in front on this as well.

A last example that’s worth a mention is the rise of experiences up the spending priorities of younger generations and families. This is coming in the nick of time for owners and operators of some big shopping malls who’re suffering from the relentless decline of retail revenues despite sustaining footfall. Some are experimenting with ideas like virtual reality experiences as a way forward. It’s a vibrant avenue for innovative business models, with plenty of opportunity for those who figure out winning solutions.

Some business models simply have to be solved

There are some blockbuster opportunities awaiting innovtive business models, but some just have to be solved. An obvious candidate that’s target rich for new business models is climate change, not least because so much depends on finding solutions that are compelling and economic. Some of this is about technology but a large proportion is not. The opportunity is open for business between nation states, business amid those with all the commodities that are involved, positively and negatively, and across society.

The pharmaceutical industry grapples with business models all the time, and the impact of this on health is widely overlooked. A primary reason for the absence of research into antibiotics is the lack of a business model that makes it sufficiently attrractive to take the risks and make the investments, since all the effort in healthcare is to limit their use.

A second challenge for pharmaceuticals is to devise viable business models around gene based therapies, when the whole sector is built on finding blockbuster molecules that can be given to the widest possible population of individuals. Arriving at pricing by dividing the cost by the number of recipents just doesn’t work with such targeted treatments. Another solution is needed, but all the technology work has been done. The heavy lifting is now needed in the development of business models that work.

Robotics and automantion? Dehumanisation as I refer to it. We know these things are coming and they’ll be many benefits over time but, as with so many big innovations, there will be winners and losers as the technology penetrates. There are obvious parallels with the Luddites resisting the advance of textile machinery in the early 19th century, except that the impact of these innovations will be more far reaching more quickly for greater numbers of people. Discussion has begun of what business models would spread the benefits through society.

Robotics and automantion? Dehumanisation as I refer to it. We know these things are coming and they’ll be many benefits over time but, as with so many big innovations, there will be winners and losers as the technology penetrates. There are obvious parallels with the Luddites resisting the advance of textile machinery in the early 19th century, except that the impact of these innovations will be more far reaching more quickly for greater numbers of people. Discussion has begun of what business models would spread the benefits through society.

Solutions to these would be of huge value, as would viable sustainable business models for health care, notably in the UK and USA, where the existing models are broken. The model for UK care homes is only sustainable at the margins with significant specialisation. The NHS was devised as a get-you-well service for static demographics, ironically at precisely the moment when the Baby Boom was hatching. The mathematics doesn’t work for the keep-you-well service it’s become for a population of rising consumption and dwindling contributors. The problems in the USA are no less significant, but perhaps the trio of Bezos, Dimon and Buffett are on to something with Haven.

This is where the really big opportunities lie

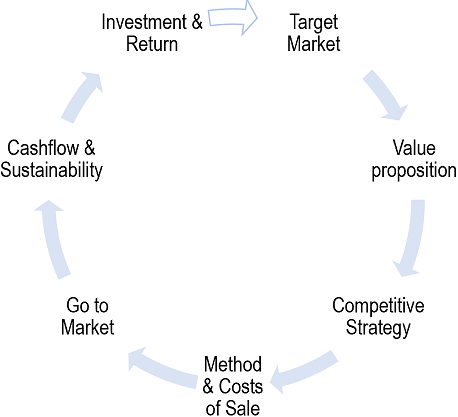

There’s a prime place for entrepreneurs to create value through innovative business models. In fact, there’s so much technology sloshing around now, that there’s been signs that the focus might shift to put the strategic emphasis on devising the right business model, and then looking for the tactical technologies to deliver through it.

Business models are where the really big waves of value lie, along with the necessary technologies, of course. Devising the right business model is essential for a winner, whether you start there or with the technology.

Blogs on: Strategy, Trends, Management

Also Interesting Reading

Peter is chairman of Flexiion and has a number of other business interests. (c) 2019, Peter Osborn.