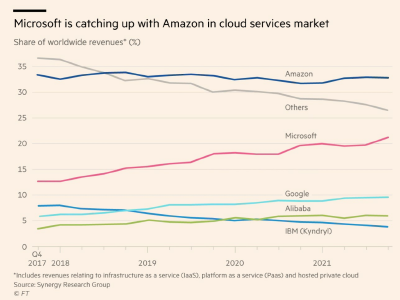

Revealing figures published recently in the FT show Cloud supply is highly concentrated in AWS and Azure, and they now command more than half the worldwide revenues in the sector. The rest of the vendors are fragmented and too dispersed for them to be able to exert any significant influence. They pick up what’s left. No European provider merits a mention and all are lumped together with the rest of the bit players in “Other”, which will show its significance in a moment.

Revealing figures published recently in the FT show Cloud supply is highly concentrated in AWS and Azure, and they now command more than half the worldwide revenues in the sector. The rest of the vendors are fragmented and too dispersed for them to be able to exert any significant influence. They pick up what’s left. No European provider merits a mention and all are lumped together with the rest of the bit players in “Other”, which will show its significance in a moment.

At its core, Cloud is essentially a commodity, with little difference between the various providers beyond price, and commodity markets usually give customers choice and control. Think petrol and diesel, electricity and gas, wheat, sugar and so on.

Of course, all Cloud providers do their best to claim that their particular compute, storage and networking services are different, but these differences are at the edges and frequently bigged up beyond their real substance. Churn reduces growth of market share, and the real purpose of these bells and whistles, particularly among the Cloud duopoly of AWS and Azure, is to discourage defections.

Leading Cloud vendors have different strategies to reduce the chances of their customers switching to a different vendor:

- AWS proprietary services and data egress charges,

- Microsoft levies charges to its business software outside Azure

- Google leverages existing use of its other services

The really insidious strategy that’s used by Cloud vendors is to exploit the inherent human preference for what’s familiar and easy – the path of least resistance – most teams prefer what they already know and can deploy with familiarity. It’s only natural. Smaller teams are always stretched for skills, too. So Cloud vendors try very hard to include all the services they can, deployed right from the dashboard. They are also vigilant and look for any outside software that users deploy on their Cloud, and then engineer their own versions with slight differences to hobble portability.

Hotel California?

All this makes easy to sign up and get started, and there are lots of enticing services that are really easy to add in. What could be better? What could be the problem with all this? So long as things stay as they are, and from a strictly engineering perspective, everything’s just great. The difficulties come from a business direction.

- Cost inefficiency

Limiting the design of a Cloud architecture to one provider is not going to search out the best price structure and dynamics. The market leaders calculate their services and pricing in a way that is largely unrelated to their cost of production. These things are carefully calibrated to extract the maximum revenue without provoking the customer into looking for alternatives. So it’s much easier to stay because attempting migration elsewhere is complex and painful.

Cloud systems can easily integrate a variety of component services from different providers – it’s called Multi-Cloud. A business approach to Cloud choices will look at how pricing of different options works with growth as a key input to selection, along with functionality and performance. The business factors that are often overlooked if design is left to technologists.

- Concentration of risk

The leading vendors all talk about “all the nines” up-time, and this, that, and the other technology to ensure zero data loss. Yet we all know that outages, hacks and other dread scenarios happen quite frequently. All your systems in one place just concentrates this risk.

Worse, if something does happen then support is often really hard to come by. Unless you’re a very large customer you’re likely to be eleventh on a list of ten.

- Loss of choice

All those extra services from the same vendor that are so easy to use, conspire to make it hard to move. Charges levied to get data back out work in the same way. They raise the cost and complexity of switching to another provider. This means that you have to be more tolerant towards the vendor you’re with than you would be otherwise, being it lack of service or onerous cost.

This loss of choice translates to reduced ability to respond to change, and whether it’s internal or external, we know that business decision making is all about change. As the CEO of Arco once said: “Business is all about solving problems before someone comes and sorts them out for you”.

It’s about competitors, not customers

Sexing up services and drawing you in so that you use only the things they supply supports their pricing power, reduces customers’ choice and freedom of action, and concentrates risk. These strategies are primarily about thwarting competitors, not serving customers. Regulators have been concerned for a long time and there’s a growing cat and mouse game.

FT.com: Microsoft’s tactics to win cloud battle lead to new antitrust scrutiny

Microsoft: Microsoft responds to European Cloud Provider feedback with new programs and principles

All this goodwill gesturing from Microsoft is restricted to competitors based in Europe, and as the chart above shows, these are minnows in the market. The real issues arise from the way the two leading players are carving up the market between them, like it or not.

Disadvantages are worst for mid-market and smaller firms

Large enterprises are highly likely to be multi-cloud anyway, with business units operating in silos, each on their own favourite Cloud, and acquisitions coming with a variety of choices made in different times. Fortunately, these organisations usually have the resources to run multi-cloud successfully because they have the scale to have the support teams and range of specialist skills.

Mid-market and smaller firms are not so well placed and the impact of problems is usually greater and they have tighter resources, which makes it harder for them to respond. So SMEs must be smart and look for techniques and strategies to retain their ability to make business choices, go for cost effectiveness, and reduce risk concentration.

The key barrier is the cost of running a fully skilled, Cloud agnostic capability in-house. Going to one of the many vendors is hazardous, though, because most of them look to have the same kind of single vendor preference as many tech teams. One glance at their website footers often shows them as being an XYZ Gold Partner or a 123 Preferred Specialist, or some such. It’s tempting to think that they are incentivised by preferential rates, too.

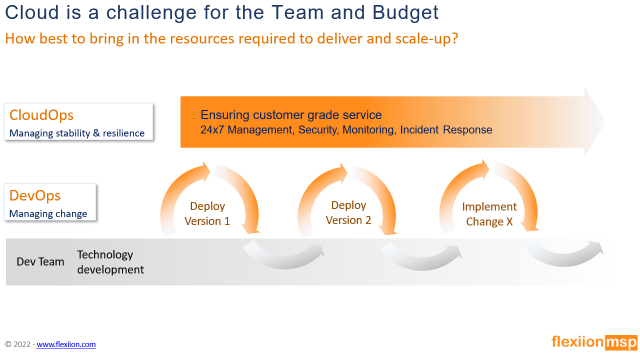

Cloud agnostic DevOps and CloudOps as a Service

A new breed of independent Cloud management firms is emerging, and Flexiion is one example. With specialists in all the major Cloud brands and technologists, available on call, 24x7x365, customers can think and act independently, and make business decisions about their Cloud choices.

- Hardware engineers to manage physical infrastructure including; servers and storage platforms

- Networking engineers to manage all aspects of physical and virtual networking

- Operating System engineers to manage operating systems including; Linux, Windows, VMWare, FreeBSD, SynologyOS

- System Application engineers to manage system applications such as: apache2, PostgreSQL, nginx, docker

- Public Cloud engineers to manage accounts and public cloud services from providers such as; AWS, Google, Azure

- DevOps engineers providing CI/CD support, design input, environment management

The business model of specialists like Flexiion delivers these teams and their support to you as a service, making it ultimately cost efficient for Mid-market and SME organisations who want to concentrate payroll on people who add prime value to their businesses, not on infrastructure functions like DevOps and CloudOps.

Affordable skills give you scalability, open up choice, and manage risk

Access to all the right skills, whenever you need them, and as an affordable service gives you scalability and freedom of choice to make business operations deliver whatever Cloud is right for where you’re going. You can navigate the business impact of the duopoly that’s carving up the Cloud market.

Peter is chairman of Flexiion and has a number of other business interests. (c) 2022, Peter Osborn